Invasive alien mammals threaten biodiversity in Europe

A joint team of international researchers from Italy, Austria and Portugal recently highlighted that invasive alien mammals are expanding their ranges in Europe, threatening native biodiversity. The review entitled "Introduction, spread, and impacts of invasive alien mammal species in Europe" has been published in the journal Mammal Review.

The presence of these species introduced intentionally as 'pets or fur animals' or accidentally in territories other than their natural habitat has negative consequences, not only on the environment but also regarding the potential transmission of pathogens, including zoonotic pathogens that can be transmitted from animals to humans. The research team found that this risk is associated with 81% of the invasive alien species studied.

The work, coordinated by researchers from the Department of Biology and Biotechnology "Charles Darwin" at Sapienza University of Rome and the University of Vienna, in collaboration with the University of Lisbon, has shown that, despite the implementation of international agreements, reports of invasive alien mammals in Europe are increasing at the expense of native species. The research consists of a systematic review of the literature published to date on 16 invasive alien species, supplemented with up-to-date information extracted from global databases.

In 2014, the European Union adopted Regulation 1143/2014 to control or eradicate priority invasive alien species and prevent their further introduction and establishment. At the core of the regulation is the Union List, a list of species towards which prevention, management, early detection and rapid eradication measures should be directed. Despite community interest in the problem, no previous research had specifically addressed the ecology of the invasive alien mammals on the list.

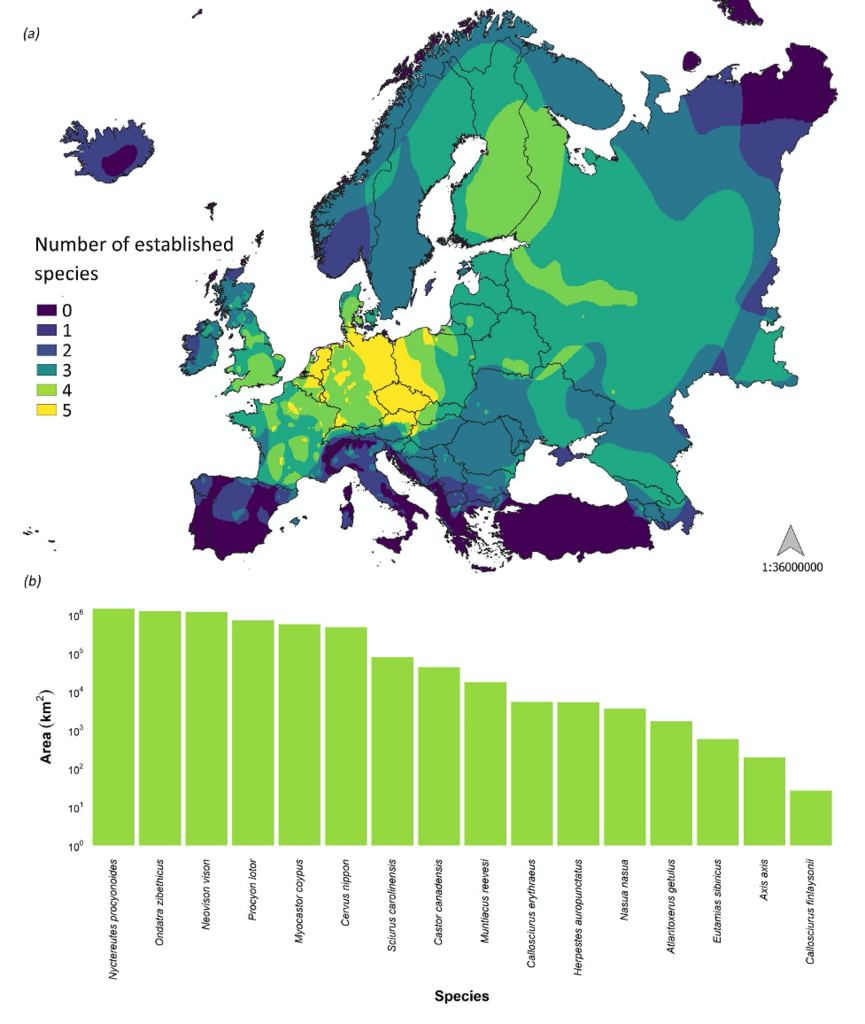

According to the authors of the review, the most widespread invasive species in Europe are the raccoon dog (Nyctereutes procyonoides) native to eastern Siberia, the muskrat (Ondatra zibethicus), the American mink (Neovison vison) and the raccoon (Procyon lotor), the latter of North American origin, which have invaded at least 19 countries and have been present in European territory for 90 years. The wide distribution of these mammals can be attributed to several factors, including adaptability, ability to colonise different environments and high reproductive capacity.

It was also found that all five species of Sciuridae (the family of rodents that includes marmots, sugar gliders, and arboreal squirrels, among others) have been introduced into Europe at least once as 'pets' or for recreational purposes. These animals are often released illegally in urban parks when people are no longer willing to keep them. The introduction could also have been for ornamental purposes, although this activity is falling into disuse thanks to awareness campaigns.

Other species such as the coypu (Myocastor coypus), the raccoon or the American mink have been introduced repeatedly to be bred as fur-bearing animals: frequent, not always accidental, escapes from farms over the years have led to the establishment of real populations in the wild.

"Although there has been a decrease in new introductions of alien mammals over the last 50 years," says Lisa Tedeschi of Sapienza University, the study's first author, "they continue to expand their ranges in Europe, aided by the illegal release of individuals into the wild, seriously threatening native biodiversity."

Another important aspect concerns the involvement of the species studied in transmission cycles of zoonotic pathogens: some infectious diseases associated with invasive mammals (such as echinococcosis, toxoplasmosis, and bailisascariasis) may threaten human health. Notable are the SARS-CoV-2 outbreaks in American mink farms in the Netherlands and Denmark in 2020, although the epidemiological role of minks (and other invasive mammals) in the virus cycle remains unclear.

In addition, the American mink also has a negative impact through predation on other species, such as the European water vole (Arvicola amphibius). Invasive mammals can also threaten the genetic heritage of native species through hybridisation (i.e. cross-breeding between different animal species). In the UK, for example, the sika deer (Cervus nippon) is threatening the genetic integrity of the Scottish subspecies of red deer (Cervus elaphus scoticus).

"Invasive mammals can contribute to the extinction of native species through several mechanisms, including competition, predation and disease transmission," says Carlo Rondinini of Sapienza University, corresponding author with Franz Essl of the University of Vienna. "The Eurasian red squirrel (Sciurus vulgaris), for example, has become extinct in more than half of its range in Italy and has been replaced by the Eastern grey squirrel (Sciurus carolinensis), while the American mink has colonised the area occupied by the European mink (Mustela lutreola), confining this native and critically endangered species to just a few areas of Spain."

Since the eradication of alien mammals with such wide distribution is difficult to achieve, it would be advisable instead to optimally manage populations of species that have become invasive and may be problematic.

"In this context," concludes Lisa Tedeschi, "identifying problem populations or areas that are more overrun than others can help mitigate future impacts."

References:

Introduction, spread, and impacts of invasive alien mammal species in Europe – Lisa Tedeschi, Dino Biancolini, César Capinha, Carlo Rondinini, Franz Essl - Mammal Review https://doi.org/10.1111/mam.12277

Further Information

Carlo Rondinini

Department of Biology and Biotechnology "Charles Darwin"

carlo.rondinini@uniroma1.it

Lisa Tedeschi

Department of Biology and Biotechnology "Charles Darwin"

lisa.tedeschi@uniroma1.it