Children in the water one million years ago: human fossil footprints discovered in a prehistoric river in Melka Kunture

Melka Kunture, 50 km south of Addis Ababa, is an important complex of Pleistocene archaeological sites located along the upper basin of the Awash River, on the Ethiopian plateau. In this area, archaeological research began more than 50 years ago, and since 2011 has been carried out by the Italian mission led by Margherita Mussi and her team of the Department of Ancient World Studies of Sapienza University of Rome.

Dozens of archaeological levels have been identified over the years, found mainly along the gullies cut by the streams of the area. In 2018, in one of these incisions called the Gombore Gully, the Sapienza team had already found numerous human footprints of adults and children, tools made from volcanic stones (such as obsidian and basalt) and remains of hippos butchered by the hominins. These discoveries, sealed by a 700,000-year-old tuff, helped the researchers to reconstruct a scenario in which children assisted adults engaged in knapping stone and butchering large animals, proving that in the prehistoric environment the acquisition of skills and techniques useful for survival began at an early age.

Today, a new study on the archaeological layers of the Gombore Gully, dating back to the end of the Early Pleistocene, offers another rare image of childhood in the most ancient periods of prehistory. The research, coordinated by Flavio Altamura and Margherita Mussi of Sapienza University in collaboration with researchers from the University of Cagliari, Bournemouth University (UK) and the Urweltmuseum GEOSKOP (Germany), focused on another site of the gully, even more ancient, called Gombore II Open Air Museum where new footprints of children were found on the edge of what was a prehistoric river. The results, which shed further light on the behaviours and habits of our distant ancestors, have been published in the scientific journal Quaternary Science Reviews.

The excavations have documented a sequence of archaeological layers about 3 meters thick, which, according to the researchers, probably formed along a river and in marshy environments, cyclically invested by ashes erupted from volcanoes several tens of kilometers away. The volcanic tuffs allowed to date the layers between 1.2 million and 850,000 years ago using the method called Argon/Argon.

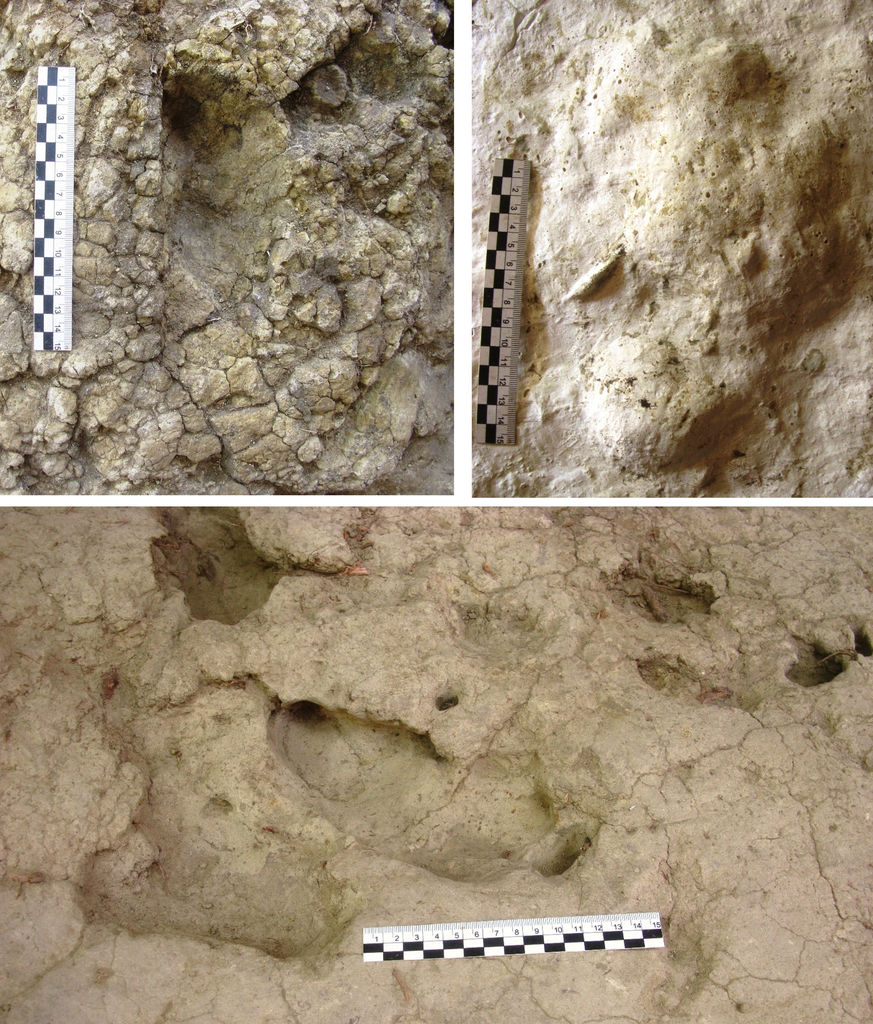

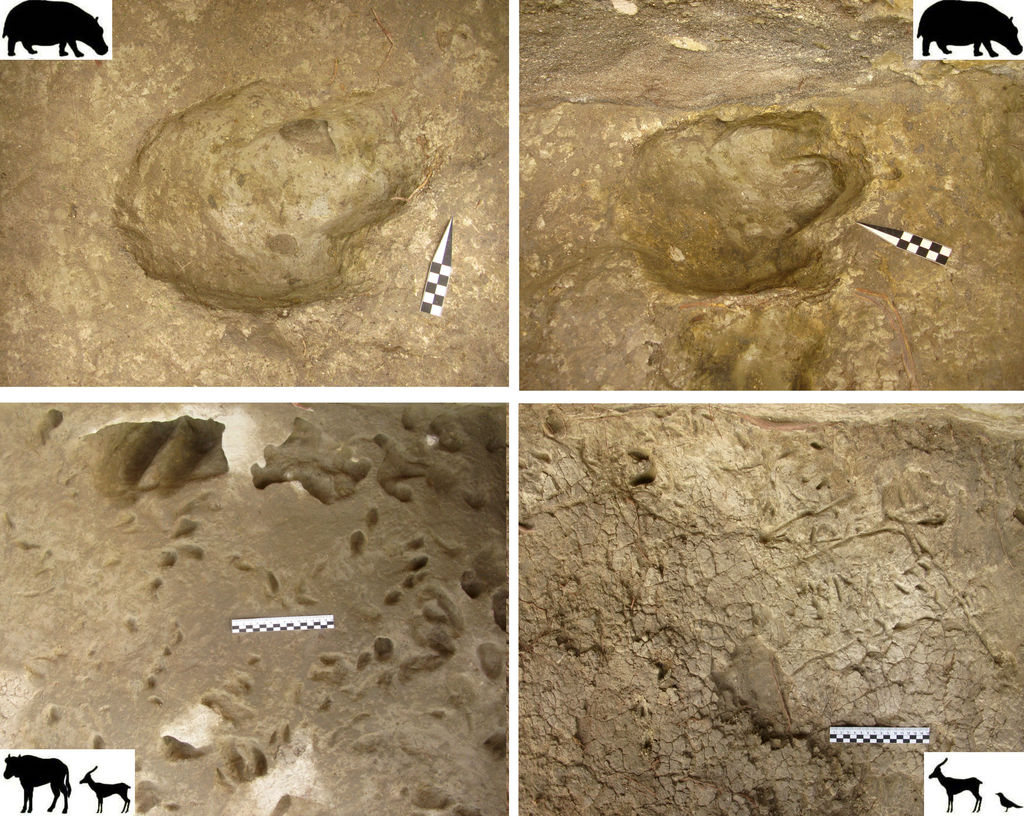

The excavations notably brought to light 18 fossil surfaces with footprints left by hippos, hyenas, some herbivores similar to today's wildebeests, gazelles and birds. Three of the levels have also revealed human footprints, almost all attributable to children and adolescents of the prehistoric human species Homo erectus/ergaster or possibly already to an archaic Homo heidelbergensis.

"These footprints - says Margherita Mussi, director of the Archaeological Mission to Melka Kunture - are among the oldest in the world and the earliest ever discovered made by children. Further proof of human presence near the river are the numerous stone tools: some obsidian flakes were probably trampled by hippos, which made them sink into the mud at the bottom of their footprints, indicating the coexistence of man and these dangerous animals."

In many levels, there are also prints formed by curvilinear trails with small almond-shaped hollows, the traces left by bivalve freshwater mussels, which live anchored at the bottom of rivers and lakes with clean and well-oxygenated running waters. This is an excellent indicator to reconstruct the paleo-environment and also allows to indirectly confirm the existence of fish, on which the molluscs depend during their reproductive cycle.

The children's footprints close to the prints of herbivores and molluscs show that the little hominins entered shallow and clean waters, as did the other animals. "Probably, even a million years ago" - says Flavio Altamura, who carried out the excavations - "the Pleistocene children entered the water for reasons very similar to those of modern children: to drink, to wash themselves or to try to catch fish and molluscs with their bare hands. Or more simply to play."

"This research, – Mussi concludes – carried out thanks to funding by Sapienza University and the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, provides a snapshot of Pleistocene childhood and confirms that the children's attraction to watery environments and ponds - puddles included! – is deeply rooted in human behaviour. This is, in a way, the first scientific evidence of "bathing" children."

References:

Ichnological and archaeological evidence from Gombore II OAM, Melka Kunture, Ethiopia: an integrated approach to reconstruct local environments and biological presences between 1.2-0.85 Ma - Flavio Altamura, Matthew R. Bennett, Lorenzo Marchetti, Rita T. Melis, Sally C. Reynolds, Margherita Mussi - Quaternary Science Reviews 244, 106506 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2020.106506

Further Information

Margherita Mussi

Department of Ancient World Studies

Director of the Italian Archaeological Mission to Melka Kunture and Balchit

margherita.mussi@uniroma1.it

Flavio Altamura

Department of Ancient World Studies

flavio.altamura@uniroma1.it