First 7000 year old genomes from the Green Sahara decoded

An international team led by researchers from the Archaeological Mission in the Sahara of Sapienza University of Rome and the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, sequenced the first ancient genomes from the so-called 'Green Sahara', a time between 14,500 and 5,000 years ago when the Sahara Desert was a green savannah, rich in bodies of water that favoured human settlement and the spread of pastoralism.

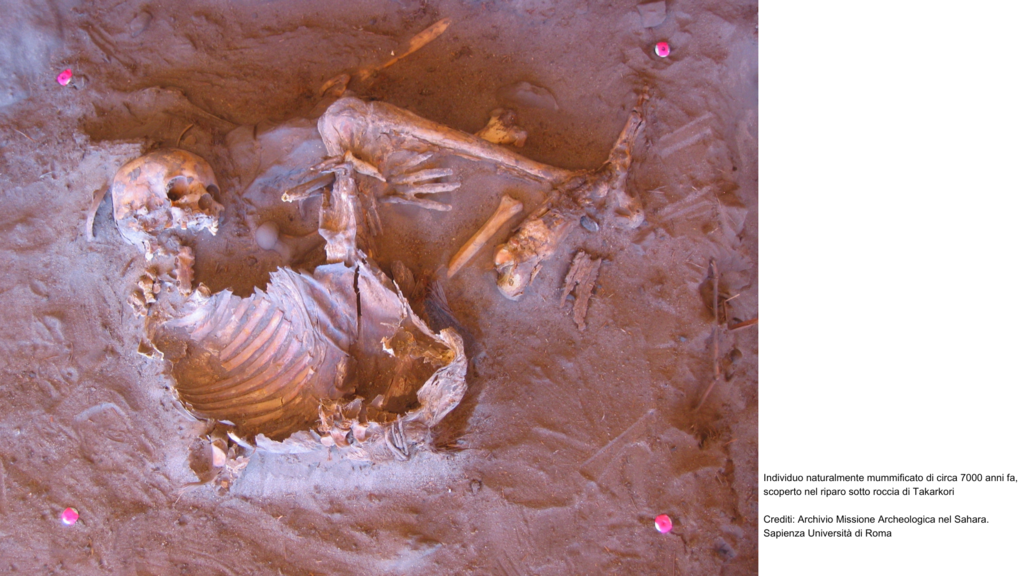

Analysing the DNA of two naturally mummified individuals from around 7,000 years ago, discovered in the Takarkori rock shelter in south-western Libya by archaeologists from Sapienza University and the Department of Antiquities in Tripoli, it emerged that they belonged to a long isolated and now extinct North African genetic lineage.

The study, published in Nature, revealed that Takarkori individuals are mainly descended from a North African group that separated from sub-Saharan African populations around the same time as modern human lineages spread out of Africa, around 50,000 years ago. This group, composed mainly of cattle herders, was subsequently isolated, showing a profound genetic continuity in North Africa since the end of the last Ice Age. The presence of a minimal genetic component of non-African origin suggests that cattle breeding spread in the Green Sahara predominantly through cultural exchange rather than through large-scale migrations, as has long been hypothesised by Sapienza archaeologists. Thus, the absence of traces of sub-Saharan ancestry in ancient genomes suggests that the area was not a corridor for the passage of North African and sub-Saharan populations but rather a place of contacts and networks.

The study also sheds new light on Neanderthal ancestry, showing that Takarkori individuals possessed significantly less Neanderthal DNA than humans outside Africa, but more than contemporary sub-Saharan Africans.

'Our results suggest that although ancient North African populations were largely isolated, they received traces of Neanderthal DNA through gene flow from outside Africa,' says Johannes Krause, director of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology and senior author of the study.

‘It is extraordinary,’ says Savino di Lernia, senior author of the study and director of Sapienza’s Archaeological Mission in the Sahara, "how the Takarkori site in Libya, excavated by the mission between 2003 and 2006, continues to yield incredible archaeological discoveries: here we have the oldest traces of milk processing in Africa, over 7000, the subject of research published in Nature a few years ago, and the oldest evidence of livestock farming on the African continent, some 8000 years ago.

The study emphasises the importance of ancient DNA for the reconstruction of human history in regions such as North Central Africa, providing independent support for archaeological hypotheses. By shedding light on the remote past of the Sahara, it increases our knowledge of human movements, their cultural relations and the mechanisms of establishing a pastoral economy in this key region.

References:

Nada Salem, Harald Ringbauer, David Caramelli, Savino di Lernia, Johannes Krause, “Ancient DNA from the Green Sahara reveals ancestral North African lineage”, Nature (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-08793-7

Further Information

Savino di Lernia

Department of Ancient World Studies