Tumours use a neonatal mechanism to progress through iron

So-called Treg cells are cells of the immune system that, instead of fighting cancer, help it to progress by accumulating at the tumour site. To multiply, however, Treg cells need energy and various nutrients. Among the required substances is iron, a vital element for all cells in the body, both those that belong there and the microbial cells that make up the microbiota. Iron is indeed involved in many metabolic reactions, including those that take place within the mitochondria, the energy powerhouses of cells. This is another reason why iron plays a key role in both the immune responses that protect us from tumours and in the deviant processes that help cancer progress.

But by what mechanisms do Tregs promote tumour growth? One was recently unveiled in a study coordinated by researchers from Sapienza University of Rome and supported by the Fondaione AIRC, the results of which were published in the journal JCI insight. The scientists led by Silvia Piconese, from the Department of Translational and Precision Medicine at Sapienza University of Rome, discovered in particular that the Treg cells involved in tumour proliferation exploit an absolutely physiological mechanism, active from the first weeks of life in newborns. After birth, there is a vigorous proliferation of this cell type, thanks to the mother's supply of iron. This growth is essential for the infant's harmonious development and immunological health.

The tumour uses this favourable mechanism, selected in the course of evolution, to its advantage. The reason lies in the fact that both neonatal and tumour Tregs expose on their surface the receptor for the so-called transferrin, the main iron transport protein in the blood.

The researchers made this discovery by studying an experimental system in the laboratory in which Treg cells had been genetically modified to lack the transferrin receptor. To our surprise", says Silvia Piconese, "we discovered that this mechanism played a role in the life of newborns before the tumour. This observation initially discouraged us because the mechanism we had identified was not tumour-specific", she continues. "Later, however, we realised that the observation was nonetheless important because it meant that the tumour uses to its own advantage a mechanism that is necessary for our life. Biology, and immunology in particular, teaches us precisely this: that no cell is 'bad' per se, not even the Tregs that help the tumour. It is simply that Tregs use mechanisms that in the course of evolution have been established as useful for the survival of the species", even though they can sometimes have deleterious side effects.

Thus, the development of Treg cells, along with the ability to regulate the immune response, also depends on the amount of iron available. The data also showed that, between metabolism and immunity, the interaction is bidirectional. Indeed, the proliferation of Treg has an impact on circulating iron levels. This, in turn, can change the composition of the intestinal microbiota that depends on iron, favouring the possible growth of harmful bacteria.

In this study, researchers have shown that when the Treg cannot take up iron, iron accumulates in the bloodstream. The bacteria living in the gut are very hungry for iron. If there is too much iron, however, this can encourage the growth of harmful bacteria.

"Our work revealed that Tregs are dependent on iron availability. This implies that it might be possible to influence the functions of these cells by modifying iron levels, for example with diet or specific drugs", says Ilenia Pacella, first author of the article.

The study was carried out by an international research team coordinated by Sapienza University of Rome, to which scientists from the Departments of Translational and Precision Medicine, Molecular Medicine, Clinical Internist, Anaesthesiological and Cardiovascular Sciences, Maternal Childhood and Urological Sciences contributed, with the collaboration of the Universities of Palermo, Trieste, Tor Vergata, the Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche (CNR), the Istituto Pasteur Italia - Cenci Bolognetti Foundation, the Istituto Italiano di Tecnologia (IIT), the Cancer Research Centre (CRCL) in Lyon, the IRCCS Regina Elena National Cancer Institute and the IRCCS Fondazione Santa Lucia, and with the support of the Fondazione AIRC per la Ricerca sul Cancro.

References:

Iron capture through CD71 drives perinatal and tumor-associated Treg expansion – I. Pacella, A. Pinzon Grimaldos, A. Rossi, et al. JCI insight – DOI: 10.1172/jci.insight.167967

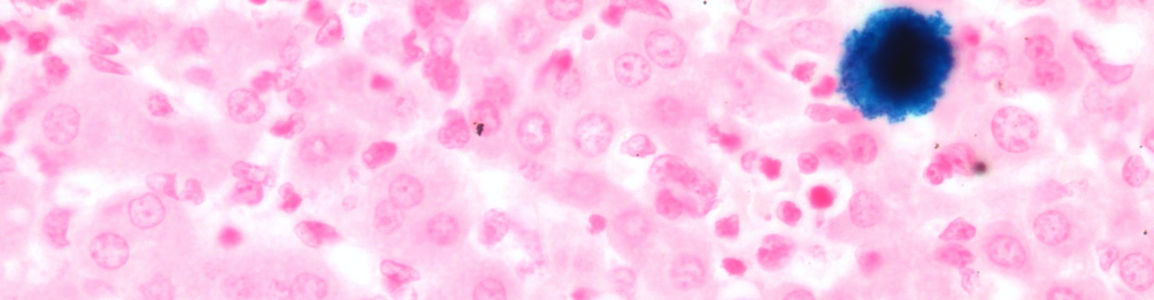

Didascalia: Immagine al microscopio del fegato: in blu vediamo un macrofago pieno di ferro (colorazione di Perls) – crediti Claudio Tripodo

Further Information

Silvia Piconese

Department of Translational and Precision Medicine, Sapienza Università di Roma